BBC sculptures: Gill, Savile, Shakespeare... and me

The Bard's radio Ariel and Prospero are back at the Beeb, but are they looking the other way?

Tempestuous times at the British Broadcasting Corporation.

Its Eric Gill sculptures at the front of the art deco Broadcasting House in London’s West End were damaged in 2022 then again in 2023 by the same person, David Chick, who shouted ‘paedophile’ as he struck the artwork.

It revives the question which barely seems to go away these days: is it immoral to separate the art from the artist’s immorality?

But since BH, as the building’s (mostly) affectionately known, is a grade II* listed building, meaning it’s of ‘more than special interest’ – I’ve tried, and failed, to work out what the ‘more than’ adds to ‘special’ – it’s possible that, legally, the BBC had no choice but to restore the work.

It was returned a few days ago, together with a protective glass box around it, which makes me think of Snow White and the glass coffin, and Mr Chick is not allowed to get within 100 metres of it.

The imagery

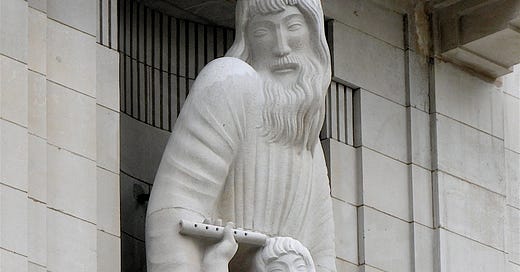

Ariel and Prospero are both characters from Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, which is set on a mystical island. Prospero is a duke-turned-magician, while Ariel is his spirit assistant with his own magical powers.

Ariel was thought by the BBC Governors to be an apt metaphor for the magic of radio when the UK got its first purpose-built broadcast centre in 1932, just 10 years after the formation of the British Broadcasting Company, as it originally was. While Ariel appeared elsewhere on the building ready for its opening, the figures at the front weren’t finally in place and finished until 1933.

It’s hard to convey to someone outside the industry just how separate the subgroups working on a show can be, and how vast an operation a complex TV show is.

The problem

Eric Gill was born in Brighton in 1882 and variously studied drawing, lettering, architecture, and stonemasonry. He became a Catholic in his thirties for the rest of his life. He died in 1940, but it wasn’t until a biography of him was published in 1989 that the facts about his sexual abuse of his two elder daughters and of his pet dog, and of incestuous relationships with at least one of his sisters became more widely known.

Even then it was only after the revelations about serial abuser and broadcaster Jimmy Savile hit the headlines this century that Gill’s misdemeanours gained a higher profile.

Savoy Hill to Savile

The BBC was originally a commercial concern, formed by the amalgamation of six radio manufacturers who wanted to sell their wares, including resonant names like GEC and Marconi. They’d worked out the obvious: you can’t sell a radio if no one’s making any programmes. So they were aiming to stimulate audio production.

What revolutionised the industry in this country, and which changed the ‘C’ of BBC from Company to Corporation, was the fallout from the General Strike in 1926. By then the young BBC was housed in the Institute of Electrical Engineers’ HQ in Savoy Hill, off the Strand near London’s Waterloo Bridge.

The reborn BBC was launched with a royal charter in 1927, at which point the radio licence fee – regular television broadcasts were still nearly a decade away – was introduced.

As well as perpetual discussions about the licence fee, the debate around BBC independence – or lack of – in the light of its taking the government side in the strike was launched. Rather than get distracted by that, may I recommend an anthropological study of the corporation, if you’re interested: Uncertain Vision written by Georgina Born, an academic and, perhaps surprisingly, a sometime prog rocker in the group Henry Cow.

Some years ago I was in a pub conversation a while after Savile’s death and the revelations of his serial sexual abuse mostly of young, vulnerable people which followed. Talking about the BBC’s staff in the context of Savile, my companion said ‘they all knew’; his unsupported claim was that everyone at the broadcaster was aware of the presenter’s crimes and actively covered them up.

Another day, another drink

It was galling to be ‘othered’ in that way as a BBC employee myself, one of around 22,000 (and heaven knows how many freelancers) and, in any case, my drinking companion was totally wrong. I interrupted him early on as I didn’t want to suffer my build-up of anger about ignorantly being accused of complicity (I’m not sure he even twigged he was speaking to a BBC employee) and, perhaps more honourably, I didn’t want him to suffer the delayed embarrassment of having to be corrected, not realising the very person he was with had vastly more experience than him of the organisation.

Cut to: more than a decade before I was at the BBC’s Elstree Centre, 13 miles or so north west from BH, and home to BBC TV’s soap EastEnders. I’d been working on the high-profile chart music show Top of the Pops, coincidentally first presented by Savile in 1964 but by this time, the 1990s, he’d long sinced cease to front it (with the possible exception of an occasional Christmas or anniversary edition).

A few of us technicians were enjoying a drink in the sunshine when a production assistant – a vital role which is literally and operationally close to the director in the TV gallery – cast a conversational cloud over us by talking about Savile as a serial abuser, to the extent that a girl had killed herself. Somewhat ironically, the PA said, ‘Everybody knows’, and not a single person out of the half dozen or so of us round the table professed to having heard this rumour before, including me.

I was shocked and appalled.

But the rumours were so low level in those days that it was possible to work with Savile and not be aware of them; I know that, because I worked on Savile’s Jim’ll Fix It a number of times as a sound technician, before that Elstree conversation, and was completely unaware of this criminal side to the presenter.

It’s hard to convey to someone outside the TV industry just how separate the subgroups working on a show can be, and how vast an operation a complex show is. Yes, I miked up Savile at various points, but I never met him outside the studio, would only ever have exchanged brief pleasantries with him while wiring him for sound, and was only one of scores of people working on that show, from lighting engineers to makeup artists to video tape editors and audience assistants.

And, as the case of senior Conservative politician Leon Brittan proved years later, rumours of sexual misbehaviour can be wrong. When I worked in commercial radio in the 1980s it was presented to me as a ‘fact’ that Brittan was a child abuser, when the record now shows he took allegations of others’ alleged crimes seriously, but went to his grave under a cloud of suspicion himself. He was posthumously exonerated and the Met Police paid compensation to his widow.

Savile = Gill?

You’re only ever likely to see Savile now on a factual programme in the context of his crimes; I confidently predict for the foreseeable that the nation’s publicly funded broadcaster is never going to repeat an entire show presented by him purely as an entertainment.

So how is it Gill’s work is still on show in pride of place at the BBC’s HQ?

I’ve wrestled with the differences between a Savile TV show and a Gill sculpture; there are many contrasts between the two, but not all of them are salient.

Savile-fronted shows were popular culture while Gill’s work has pretensions to a higher form of art, yes. But over time popular culture shows acquire a longer tail in the realm of social history. The BBC rues the day when it used to wipe tapes of, for instance, Dusty Springfield performing; her stock has risen, especially among musicians, since her death. (Savile’s stock, by contrast, has clearly plumeted but so has Gill’s – so the cultural argument doesn’t seem to hold water.)

There’s the passage of time: many of Savile’s victims are still alive, while Gill’s almost certainly aren’t. But the question of integenerational trauma arguably could nullify that distinction.

There’s the legal question previously referred to: the obligations conferred on the BBC due to the original Broadcasting House being Grade II* listed. Clearly, there’s no legal obligation on the BBC to show any particular entertainment programme. But I still don’t feel that’s the whole story.

I wonder if the real difference comes down to faces and identities. There would be outrage at Savile staring out from screens doing his performative schtick as entertainment, whereas the faces looking out from the BBC’s art deco masterpiece are of Prospero and Ariel, and not Gill himself.

So perhaps the person ultimately venerated by the sculptures of The Tempest characters is Shakespeare. And his stock stands pretty solid.

Logo

Apart from the potentially lethal psychic damage wraught by Gill on his victims, the tragedy is he has also undermined the brilliance of his own work. A previous iteration of the BBC logo used Gill sans – a beautifully clean typeface of Gill’s, where the sans, short for sans serif, from the French meaning ‘without’ and a Germanic root of ‘line’, refers to the lack of projections at the end of the letters’ strokes which can clutter up some fonts.

My hunch is the BBC foresaw the coming storm and changed its logo’s font accordingly; the change is only subtle, with the typeface also being sans serif.

Shakespeare is associated with another London landmark, the Globe Theatre, and Gill’s Ariel and Prospero stand on a globe. In As You Like It the playwright said, through character Jacques, ‘all the world’s a stage’, and talked of many entrances and exits, and of our final scene as being ‘mere oblivion/Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.’

75 years after his death, the calligrapher and sculptor continues to bequeath us an unwanted gift.

Gill sans morals.

By coincidence I'm about half way through David Hendy's "The BBC A people's history". He only mentions Eric Gill once in the context of his "The sower" in the lobby.